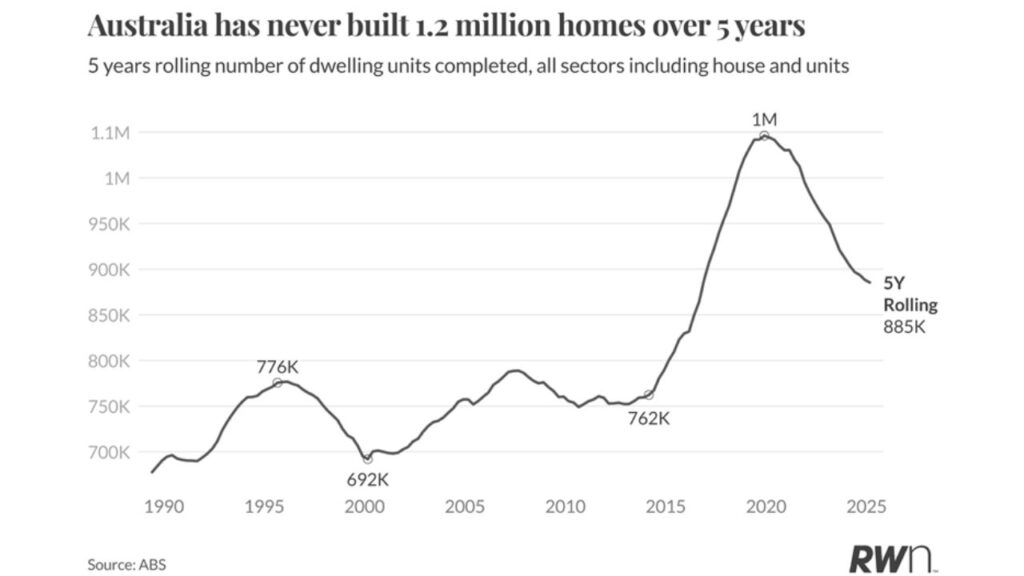

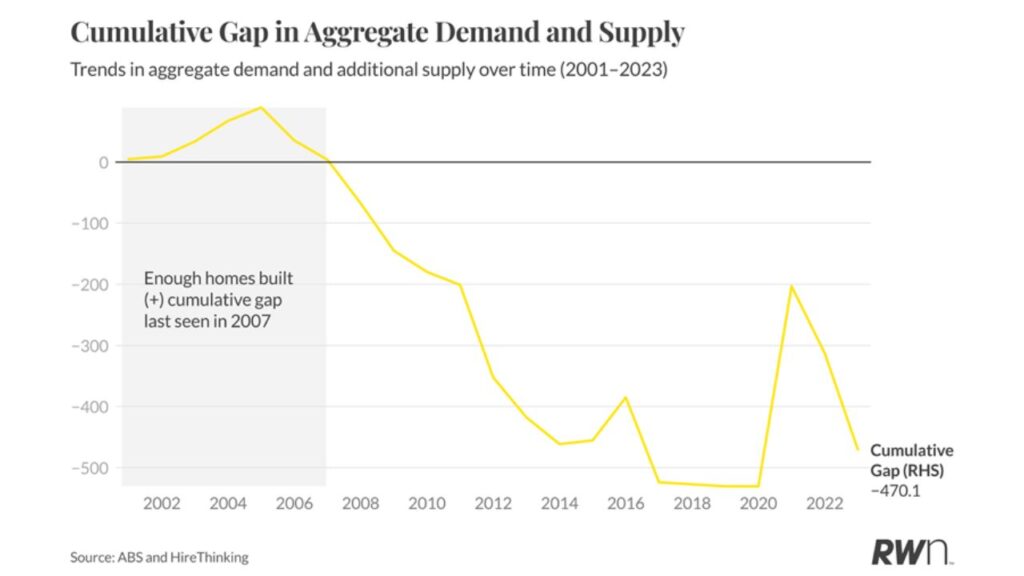

The Federal Government’s goal to deliver 1.2 million homes over five years is the right one – it would finally allow us to catch up on the homes we haven’t built since 2007.

The challenge is not in the target itself but in the capacity to achieve it.

We have underbuilt for almost two decades. Even if demand moderated, we would still need to deliver around 225,000 to 240,000 homes each year to restore balance.

Completions currently sit closer to 190,000. The deficit grows every year we miss that mark.

The workforce required to reach that level of output simply doesn’t exist.

The Housing Industry Association estimates that meeting the national target would require an increase of about 30 per cent in skilled trades.

That’s before accounting for retirements or workers leaving the industry.

Even with record migration, faster training and higher participation, that kind of growth is implausible.

It means the problem isn’t just about policy or approvals – it’s about productivity.

Each new home still requires dozens of tradespeople on site, working in sequence, with limited efficiency gains from one project to the next.

Productivity in the construction industry remains particularly problematic.

Analysis by the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) has shown that labour productivity in construction (output per hour worked) grew by only 17 per cent between 1995 and 2024, while labour productivity in the broader market sector grew by 64 per cent over the same period.

The solution to both a lack of labour and low productivity lies in changing how we build.

Modern Methods of Construction, known globally as MMC or modular building, shift much of the process off site.

Walls, floors and entire rooms are manufactured in factories, transported to site and assembled in days. It’s faster, cleaner and requires fewer workers on site. The system substitutes labour with precision manufacturing.

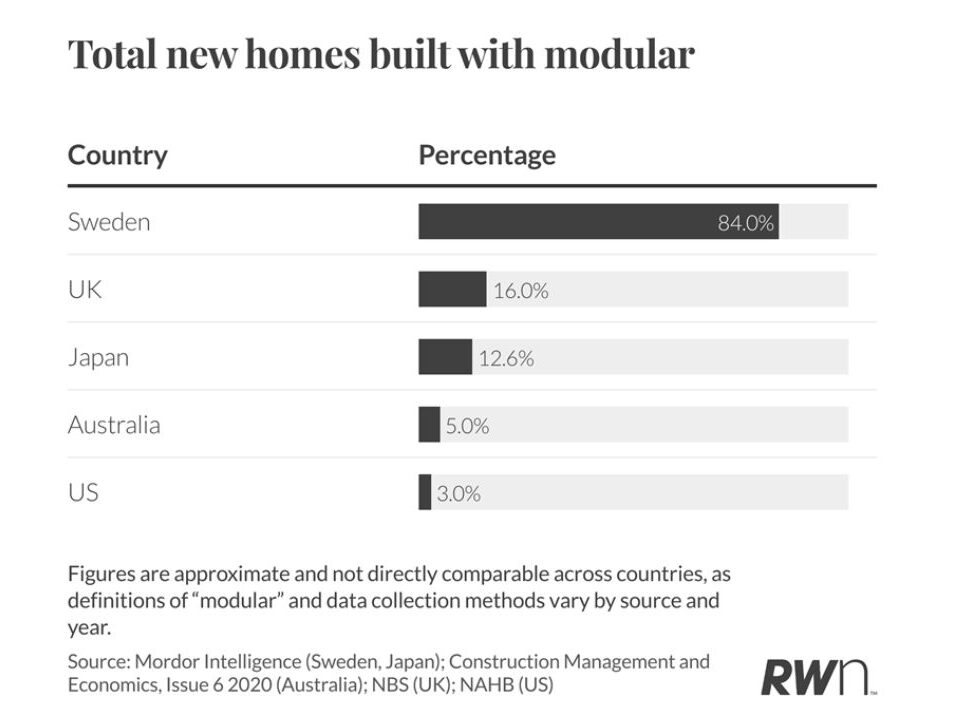

Australia currently has low take up – only around five per cent includes some sort of modular construction. In Sweden it is particularly high at around 84 per cent, Japan sits at 13 per cent, the United Kingdom at 16 per cent, and the United States around three per cent.

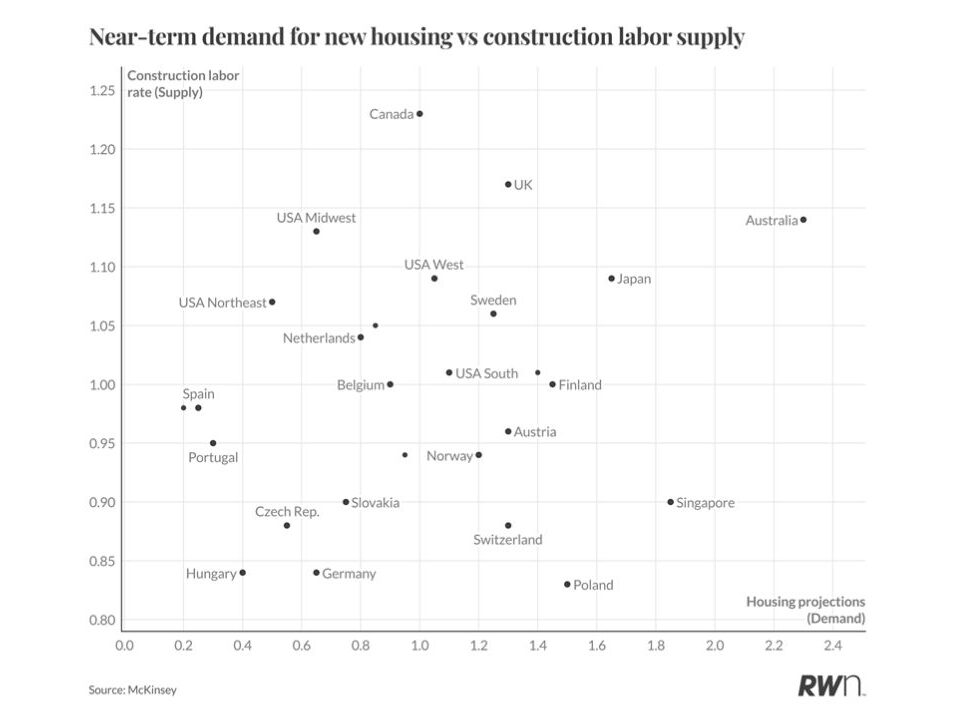

The irony is that our conditions – high wages, labour shortages and strong housing demand – are exactly those that make modular construction work elsewhere.

In fact, consulting company, McKinsey, identified Australia’s east coast as one of the most suitable markets in the world for modular construction, alongside California, London and Germany’s major cities.

Regional Australia is even more suited. It’s far harder to attract skilled trades to smaller towns, and transport costs add time and expense to every build.

Modular construction reduces that friction. Factories located near regional centres can produce homes and building components year-round, delivering them across multiple communities with minimal on-site labour.

The approach also improves consistency.

Quality control is tighter in a factory environment, weather delays are eliminated, and waste is reduced.

The result is lower costs per unit and a faster path from approval to completion.

The Federal Government recognised this reality in the 2025 Budget, setting aside funding to expand modular and prefabrication capacity.

The intent is to build the industrial base that can deliver homes at scale, reducing dependence on on-site labour.

It marks the first national policy acknowledgement that housing targets can’t be met using traditional methods alone.

Automation and robotics are at the centre of that transformation.

Modbotics, an Australian company, is already using robotic arms and digital design to cut, lift and assemble building modules with millimetre accuracy.

Tasks that once took crews of tradespeople days can now be done by machines in hours.

Each factory worker becomes many times more productive.

This shift is not about replacing workers but about using labour more efficiently.

In an industry where productivity has barely lifted in decades, greater use of technology and manufacturing methods offers a practical way to do more with the same workforce.

Australia’s housing challenge is ultimately one of capacity. Meeting national targets will require faster, more reliable delivery, and that won’t be achieved through traditional, site-based methods alone.

Modular and automated construction can increase output without adding proportionate labour or cost.

Housing affordability depends on supply, and supply depends on how effectively we can produce new homes.

The next phase of building in Australia is likely to involve a quiet transition – from work done almost entirely on site to homes assembled largely off it.

Whether or not a robot builds your next house is less the question; it’s how technology will help make sure it can be built at all.