Former Prime Minister Paul Keating isn’t alone in wanting the Reserve Bank to do much more to ensure economic recovery.

In an opinion piece for major newspapers he has said it ought to be directly funding government spending rather than indirectly by buying government bonds from third parties.

But we think there’s something else the Reserve Bank can do.

Governor Philip Lowe is right to call on governments to spend more, creating “fiscal stimulus”.

But we don’t think that absolves the Reserve Bank of the need to provide more “monetary stimulus”.

Simply put, the Reserve Bank needs to create more inflation. Quite a lot more.

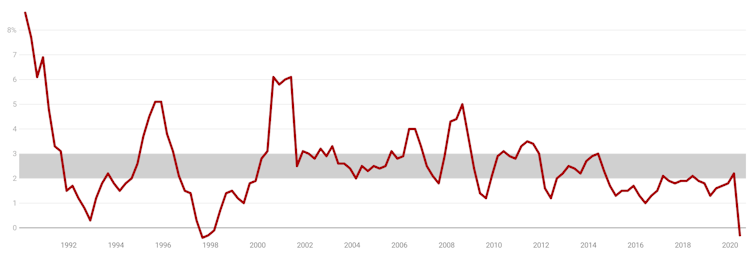

For years now, the bank has chronically undershot its inflation target of 2 per cent to 3 per cent per year. This has to stop.

Consumer price inflation since the Reserve Bank’s 2-3% target

Inflation plays a vital role in government finances, through its influence on nominal income growth. Higher nominal income growth lowers outstanding debt as a fraction of income.

To appreciate the size of the effect, if average inflation runs at 1.5 per cent per year rather than 2.5 per cent per year (the bank’s central target), after a decade prices will be roughly 10 per cent lower.

As a consequence, public debt as a fraction of national income will be 10 per cent higher, and that’s before taking into account the revenue implications of lower inflation.

Too much inflation creates its own problems, but so does too little.

Of course, the Reserve Bank’s options are limited right now. Short term interest rates are effectively zero and can’t go much lower without turning negative, an idea the bank has so far resisted.

The bank needs to commit to “too much” inflation

But there are things the bank can do, and they involve making clear its plans for when inflation recovers.

When economic growth revives, be it in 12 or 24 months, the bank will face a choice between raising rates to more normal levels, or continuing to keep them extraordinarily low.

The RBA should do the latter and promise serious inflation, more than it is comfortable with, for some time to come.

Promising to overshoot its target band will raise inflation expectations and then inflation itself, lowering the real interest rate.

This will buttress the recovery, supporting economic growth. It will also greatly improve the state of government finances.

How much inflation should the RBA generate?

It should aim for average inflation of 2-3 per cent over a long window, at least 10 years.

This will place a clear upper bound on how much inflation is appropriate over the long term, while requiring substantial inflation for some time to make up for the sustained undershooting of its target.

It’s being tried in the United States

Such a policy might sound unusual. And there would be protests about credibility and the risks of changing institutional arrangements during a crisis.

But the United States Federal Reserve recently adopted such a policy after an extensive review.

There’s no reason Australia’s Reserve Bank couldn’t do the same.

As it happens, hardly any formal change is required. Its Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy says its goal is 2 to 3 per cent inflation “on average, over time.”

So there’s no need to change the wording, merely the interpretation.

It could make clear that a practical change had taken place by referring to the new regime as a “price-level target”, since targeting inflation over a long time is equivalent to targeting a path for the overall level of prices.

It’d hold the bank to account

Regardless of the label, such a clearly enunciated approach would make monetary policy more effective and help the government with its finances.

And that’s not all. An average inflation target would provide a clearer benchmark against which to assess the bank’s performance and thus strengthen the accountability of one of our most important institutions.

Too often in the past the bank has excused its failure to hit its inflation target by appeals to a vague and shifting list of factors outside of its control.

While some excuses may have merit, the existing regime does not well communicate how such undershooting determines what the bank will do in the future.

By contrast, an average inflation target would clearly communicate that whatever the excuses for undershooting, future policy will be set to overshoot until average inflation is back on target.

It’s appropriate for fiscal policy to take the lead right now. But monetary policy has to be ready to do its job too.

This article is by Chris Edmond and Bruce Preston, Professors of Economics, University of Melbourne. It is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.